For many breweries that opened in the early to mid 1990s, surviving was the key. Sure, there are a lot of successful and well-known names that was birthed in that time frame and have risen to be some of the biggest volume producers in the country. Stone, New Belgium, Dogfish Head and Oskar Blues now are in the Top 20. They were just a few of thousands of brew pubs and production facilities that opened its doors at the dawning of the Internet and the rise and fall of grunge rock. Many among those thousands opened and closed, a blip on the radar. Others have passed their 20th anniversaries or are on their way soon. Their stories show how craft breweries found a footing in the American beer landscape as well. A lot of the survival came because those breweries that stood above the rest relied on quality, helping reform decades-old laws on the book and educating their consumers.

“We got [the brewery] opened just in time for the industry to start crashing,” recalls Gene Muller, who opened Flying Fish Brewing in Cherry Hill, New Jersey in 1996. He added the story of a 7-barrel brewery out of Colorado that was sending bottles to New Jersey soon after opening.

“Those bottles were exploding on the shelves,” Muller said, who before opening his brewery worked as a writer for New Brewer Magazine. “There was no thought to quality control and people shipped everywhere. We set up a lab from Day One and really focused on that.”

The first brewer hired for Flying Fish came from Oregon’s Deschutes Brewery. Joe Pedicini did a lot of lab work while at Deschutes and both he and Muller stressed that quality would win out.

“We have been focused on it for a long time and we have just expanded in our capabilities,” Muller said.

For Grand Teton Brewing, which started in 1988 as Otto Brothers Brewing but rebranded a decade later to what it is now, it felt like a new brewery in its move from Wyoming to Idaho that needed to shake the image of bad quality, which had the brewery lose half of its production volume at one point.

“We certainly felt the hurt as breweries began to pop up left and right,” said now brewmaster Max Shafer. “We fought with our own problems internally — mainly around quality. We wanted to grow and grow and grow and we hit the beer boom in the hay day. While trying to do that, our quality went way downhill.”

Shafer said it took nearly another decade to really break the idea that the Grand Teton brand put out sub-quality beer.

“Now, people always tell me how they buy our beer because ‘they know what they are getting,’ “ Shafer said. “I take that to mean they know it will be tasty and the same as it was the last time they bought it.”

For some breweries that have lasted, educating its customers was task No. 1. In Connecticut, Willimantic Brewing president David Wollner, who opened ‘Willibrew’ as a craft beer bar first in 1994 and expanded to making one beer on site starting in 1996, getting people to understand what local craft beer even was took effort.

“The Bud drinker, light beer drinkers, it was a journey for me to convince them, first that making beer right in town is as fresh as it’s going to get,” Wollner said. “It took a lot of effort by bartenders and servers to even get them to taste our Certified.”

One thing that Wollner said that he decided to do different than some opening breweries: he made one beer.

“We didn’t have five standard beers, a light, a Brown, a Red and a Stout and a seasonal, we just made Certified Gold Golden Ale,” he said. Since the brewery was also a beer bar it could rotate in other breweries and styles.

“Little by little, by the time they took the third or fourth sip they were looking to buy a second pint,” Wollner said. “I think a lot came down to the freshness on hand.”

Wollner remembers another brewery opening in town that didn’t last.

“People were just opening breweries to make money … the brewer was a retired optometrist who took a two-week course at Siebel to learn to brew and they made beer and it was awful,” Wollner said. “It was all over the place, no technique, the bottles would explode on the shelf.”

He even served the beer in his beer bar and he said customers would try it once.

“The consumer was a lot less educated, but they knew what an Amber or Red should taste like,” Wollner said. “The brewers sometimes didn’t know a lot and the consumers knew even less.”

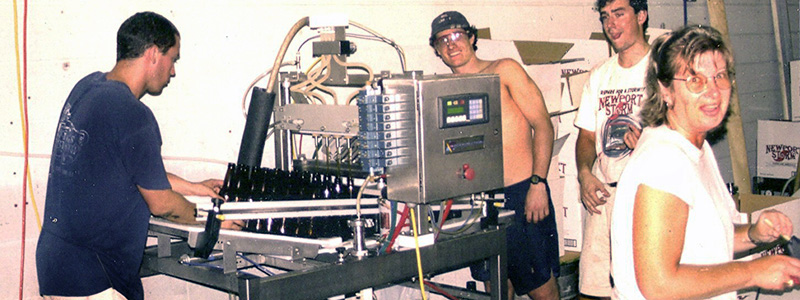

In Rhode Island, taprooms were yet to be allowed in breweries — you either owned a brewpub or you had a production facility — so Newport Storm Brewing’s Brent Ryan and partners opened a production site with just one beer being made, their Hurricane Amber Ale.

“The biggest challenge we had was explaining what craft beer was,” said Ryan, the brewery’s president and co-founder who was 22 when the brewery opened in 1999. “There wasn’t a lot of sales going on, Rhode Island was a craft beer wasteland, so it’s wild for us that we made one beer for two years to start. We didn’t do it because it was cool and it was a marketing ploy. It was difficult enough to get people to carry that one beer. Their willingness was limited at best. Back then, getting on anywhere was big. We would get in the cooler door of a liquor store, they put us in with the domestic light beer since it was where most people shopped in. We didn’t know any better. In fact, we just got moved into the craft beer section after 17 years at the same liquor store.

“While we weren’t one that opened in 1992 or further ahead of the curve, we felt that we were ahead since Rhode Island was behind. In ‘99 some states had the scene, but we really had to explain what we were. It’s laughable now to think of Sam Adams as “local” here in Rhode Island, but that’s what beer menus had it listed as then.”

Law changes in the mid 90s killed what growth there could have been for many microbreweries said Dunedin Brewery president and founder Michael Bryant, saying that Florida is still a frontier of sorts for craft beer some 20 years later.

“Brewpubs were doing good as they had the full revenue of on-site retail sales to promote their on site brand sales,” he said. But that changed as laws forced breweries to go through a distributor instead and it restricted the types of bottles that breweries could sell, namely restricting 22-ounce ‘bombers.’

“The micro breweries suffered, the inability to self-distribute meant they could not bring in the revenue to efficiently promote or develop its brands,” Bryant said. “Also the state law restricted bottle size to only what was OK for the large manufacturers, this robbed our small brewers the use of the [bombers] that was the visual banner of the small brewery renaissance at the time.”

Bryant and others jumped into lobbying efforts with the help of the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) to help modify the bottle law.

“I was president of the Florida Brewers Guild after lobbying successfully for the bottle law and members were very concerned we would all now have more competition for shelf space and taps and more would go out of business,” he said. “My answer to the members concerned was that the rest of the domestic small breweries and imports will now help us develop the palette of the Florida beer drinker. At that time big domestic beer was the beer of choice for about 95 percent of the Florida beer consumer base. I further stated that what will matter in the future is freshness and that breweries outside of Florida cannot provide this freshness.”

Dunedin never could get its brand promotion tempo where they needed it with the laws in place, Bryant said, so the brewery pulled its brands off the market to regain possession from wholesalers and started to focus on on-site sales instead.

“We desire to stay our own culture,” Bryant said “We have focused on our fans and what they like: The beer, the food, the music and events they respond to. We actively try not copy or follow others trends and stay relevant to our culture of fans. We believe there is a bubble somewhere and sometime for those not true to their brewer’s art and culture what ever it should be.”

With the talk about “a bubble” always on the horizon, the breweries see different concerns rising now than when a crash of breweries happened in the mid-90s.

It depends on the size you want to be, Wollner said.

“All the small towns had breweries before,” he said. “You build your system based on the population. If you have 5,000 people you only need a three-barrel system. You have 50,000 people, then you have a 10-BBL system in. There is no reason a town can have 10 pizza places and they all seem to do some business. I can see where you could have one in every town where they all have their own flavor and their own way of doing things. Will they all make oodles of money so that AB will come in try to buy them? Probably not.”

Most owners of breweries now recognize that there is less volume per account for everyone since everyone is selling more beer per account, so you need more accounts. Some people have been solving the puzzle with pricing.

“Before, $6.99 was an expensive six pack and now people will pay $15 for a four-pack and a lot of people are getting that,’ Ryan said. “In that sense, couple with what people are doing at retail and we realize that you don’t have to be a 10-15,000, or even a 50,000-barrel brewery to have a solid business. There are ways to cover your expenses and make up that revenue in today’s environment. Two of those ways are what you sell out your door at full retail margin or wholesale at $30-50 dollars per case. When we started out we sold it at $17 per case to push the limit. Now that’s not just because of 30-50% inflation either, you are seeing 100-300 percent increase in the pricing. That has created some room for people to exist on a scale that we couldn’t have done in 1999.”

Muller said yes there is some problems looming, but he called the problems ‘same but different.’ Pricing a brewhouse and putting together a business strategy is now cheaper than ever.

“We started with $750,000, and that was barebones,” Muller remembers, saying a second round of financing of $200,000 helped as well. “Now someone can pull 30-40K and get a 1,500 square foot warehouse and you have a brewery.”

“It’s like an expensive hobby for them. And I have seen some where it became a real business, but I have seen some where I don’t see how it can ever become a real business either, or if they want it to.”

Muller feels there are a lot more hobbyist involved now, but those types will go away.

“People that start now and ‘get it’ and do a good job starting small, you can see the focus on quality, consistency and I think that is what going to give them staying power,” he said.

Shafer echoed on the importance of lab work, quality and consistency.

“We focus on our quality and consistency because we know one bad pour of any of our beers, and folks won’t return to our brand,” he said. “Our Ale 208 is a simple beer and it can’t hide any flaws. Idaho isn’t the greatest craft drinking state, so most people reach for macro brands which are flawless beers every time and they know what they are buying. Ale 208 has become one of the biggest brands in the state and I attribute that to our process — we make the same beer each time, inviting the consumer to return for another pint or 6 pack. The minute we lose that, we are at risk of losing sales and the same goes for every craft brewery in the US.”

1 Trackback / Pingback