As a brewery pushes beyond their own taproom walls and into wider distribution, one question becomes increasingly difficult to answer: Who controls the story once the beer travels farther than the people who made it?

Inside a taproom, brand identity is immersive and intentional. The staff tells the origin story. The design choices reinforce a sense of place. The surrounding landscape becomes part of the narrative. But once cans land on retail shelves, sometimes hundreds of miles away, the brewery loses that controlled environment. The story must survive in inches, not acres.

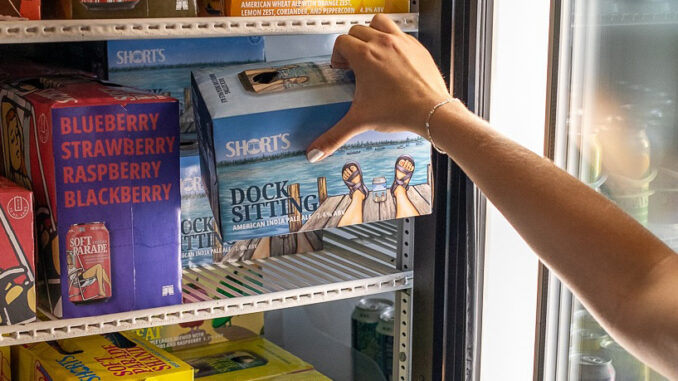

For Short’s Brewing, a regional brewery based in Northern Michigan with distribution across the Midwest, that tension is constant. Director of Brand & Marketing Christa Brenner said the challenge is finding ways to compress an experience into packaging and digital touchpoints without diluting what makes the brand distinct.

“We have ’Short Stories’ on our can,” Brenner said. “We really do try to show, as far as brand touchpoints, a little taste or a little flavor of who we are. We’ll try to tell a lot of that brand story through our social media, to connect with people before they’re going into the stores and getting that on the shelf.”

That pre-retail storytelling is intentional. Brenner recognizes that once the product is on a shelf in Illinois or Ohio, Short’s can no longer rely on taproom staff or the northern Michigan landscape to fill in context. The can itself, or the digital ecosystem surrounding it, must do that work.

Yet the farther a brewery expands, the more fragmented that message can become. Distributors prioritize velocity. Retail buyers focus on category placement. Bar staff rotate quickly and may have little training on brand backstory. In that environment, even well-crafted packaging can struggle to compete with price promotions and novelty releases.

Complicating matters is the craft drinker’s appetite for constant newness. Brenner said the internal debate is often less about geography and more about portfolio focus.

“We have so many beers in our portfolio,” she said. “Do we want to release some weird new beer that we’re not really sure about, or do we want to do something that’s tried and true and trusted? That’s a bigger debate for us.”

For regional breweries, that tension between experimentation and consistency directly affects brand clarity. A taproom can absorb oddities and one-offs because staff can frame them in real time. On a distant shelf, however, too many divergent labels can blur the brand’s core promise. The consumer who encounters the brewery for the first time in a grocery store does not see the internal debate; they see a single brand and judge it accordingly.

Short’s leans heavily on a sense of place to anchor that identity. Its Northern Michigan roots are not a marketing garnish but a foundational element. Brenner said protecting that lifestyle positioning has required resisting attractive expansion opportunities.

“One of the biggest parts of our brand identity is our Northern Michigan lifestyle,” she said. “Our locations are out of the way. We are not close to anything and there is no Lyft. We can’t tell you how many times folks have offered up locations and suggested satellite (locations).

”Loving where we live is the reason we exist.”

Expansion can create pressure to conform and to open more urban satellite taprooms, or to soften geographic messaging for broader appeal and chase trends that travel better than terroir. Each decision may drive incremental revenue, but over time those compromises can erode what made the brand distinctive. The farther a brand travels, the more discipline it requires.

That discipline often begins with codifying non-negotiables. What elements of the brand must remain constant regardless of market? Is it a geographic identity, a tone of voice, a design system, a core lineup, or a values-based commitment? Without formalizing those guardrails, distributors and sales teams will fill the void with whatever narrative is easiest to sell.

Operational alignment also matters. Brand standards cannot live only in a marketing department. Sales teams need concise positioning language and distributor partners need onboarding that goes beyond price sheets. Retail activations should reinforce and not contradict a brewery’s core story. If the taproom emphasizes craft, community and place, but off-premise displays focus solely on discounting and novelty, consumers could receive a mixed signal.

Digital channels offer another lever. Brenner told Brewer that Short’s uses social media to connect with customers before they reach the shelf. For smaller breweries, consistent storytelling across owned channels can build recognition that travels across state lines. When a consumer encounters the product in a new market, prior digital familiarity can bridge the physical distance from the taproom.

READ MORE: How to Rethink What Branding is for Your Brewery

There is also a structural question that many breweries overlook: portfolio architecture. As brands expand geographically, simplifying the core lineup can strengthen your message retention. A clear flagship hierarchy, consistent visual cues and restrained seasonal strategy help first-time buyers quickly understand what the brewery stands for. Complexity that works locally can create confusion regionally.

And brewery leadership must be willing to say no. Brenner shared about resisting satellite locations to illustrate that brand protection is often less about clever messaging and more about strategic restraint. Growth that conflicts with identity may generate short-term gains but weaken long-term brand equity.

The taproom may offer the fullest expression of a brand, but the shelf is often where the relationship begins. The breweries that scale successfully are those that treat distance not as an excuse to soften their identity, but as a reason to define it more clearly than ever.