If a brewery can’t reign in quality and consistency, consumers will move on.

That’s why chemistry has become such an integral part of a brewery, even on the smaller side of commercial sales.

As a brewery grows and more capital can be invested into a lab program, bettering a product can happen. Yet, not all breweries can afford expensive equipment, dedicated rooms for a lab or even hire someone with a chemistry background.

Kathy Towns, the quality manager at Texas brewery Real Ale, said that the brewery dedicated space when the original facility opened in 2006, but it was only used for storage until she started the quality program in 2007. At the time, she started by doing yeast counts and basic microbiology while eventually adding an informal sensory program. It led to more tests for IBUs, SRMs and headspace air as the company purchased more instruments.

The QA staff at Real Ale consists of her, a chemist and a microbiologist. She said all the staff makes sure to also perform quality checks in their areas.

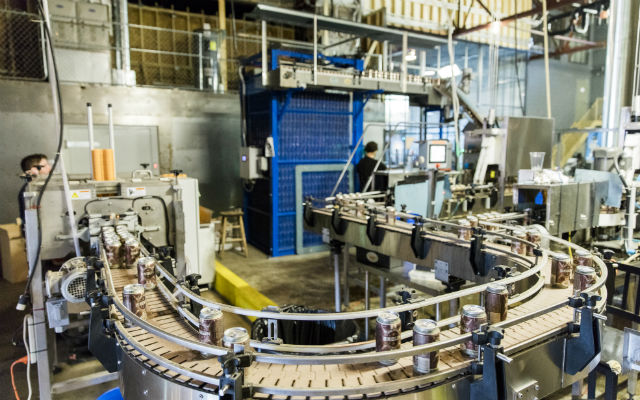

“We’ve set up quality stations at different points on our packaging lines to test things like can seams, headspace air, crown crimps,” she said.

For Ale Asylum’s Joe Walts has seen the Wisconsin brewery’s dedication to quality increase since joining in 2010, adding equipment for counting viable yeast cells, a pH meter, a combined oxygen/CO2 meter (gehaltemeter) with a bottle/can piercer for testing oxygen and CO2 levels of purged tanks and beer throughout the process, a membrane oxygen meter for measuring dissolved oxygen of wort, and a manual titration device for testing water.

Prior to 2010, he said the staff’s only measurements made were ingredient weights, gravities and pre-boil kettle volumes.

Being proactive rather than reactive is what drives Short’s Brewing’s Director of Quality, Tyler Glaze.

“The only testing we did in early 2011 was micro and we only did it if there was a problem to diagnose the issue,” he said. “When I came on board, we changed from a reactive to a proactive approach to quality and test all of our beers for contamination several times during fermentation and packaging.”

Currently the Michigan brewery’s lab is located in a 12×12 room right next to the production floor. A day in the Short’s lab consists of monitoring fermentations, testing for vicinal diketones (VDK) in fermenting beers, routine microbiological testing for possible beer spoilage organisms, shelf stability tests, bottle and can testing for dissolved oxygen content, headspace oxygen and contamination of the fillheads, and IBU and color testing of packaged beer to ensure consistency in each finished product.

So what can a brewery do?

MadTree Brewing’s Trent Leslie noted that a brewery’s lab doesn’t have to be extravagant. even un-dedicated space is beneficial if you look at Charlie Bamforth’s “Standards of Brewing,” book he says.

“The cost of quality in a brewery is typically 5-25 percent of the cost of sales,” he noted. “These costs are incurred with or without the presence of a lab because a cut in the quality program results in more lost product, recalls, and damage to reputation. A lab — which can literally be the size of a closet or no defined space at all — is meant to prevent these losses, thereby saving the brewery money.”

He did point out though, that there is an optimum amount to spend before the cost of a lab outweighs the financial risk of losing a batch.

“It would never be a good decision for a 1,000-barrel brewery to invest in a $50,000 gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy,” he said.

Here are some tips on improving quality by improving a brewery’s lab, even if that brewery doesn’t have a staff member dedicated to quality.

Where to start: Along with the microscope and hemocytometer, breweries should have a pH meter on hand along with a autoclave.

“I might catch some flak for ranking pHs above counting yeast cells,” Walts said, “but collecting samples of yeast that are representative of an entire slurry is still a problem for brewers who count cells — including myself — and as long as brewers treat their yeast well, a lot of pitch rate-related issues can be eliminated by using typical viable cell counts and pitching by weight. But pH, on the other hand, can give brewers immediate feedback about a wide range of processes.”

With water from a hot liquor tank, someone can perform sensory tests for vicinal diketone (VDK) with a small cooler, some glassware from the bar and aluminum foil.

“Brewers should also get in the habit of shaking out CO2 and settling yeast from their gravity/VDK samples,” Walts said. “Growlers are great for this.”

On the more expensive side would be DO and CO2 meters.

Towns also noted that the cheapest way to check quality is on a brewer’s head: their nose and tongue.

“You have a very sophisticated instrument right in your head,” she pointed out. “It is absolutely essential to taste your beer all through the process.”

Spectrophotometers are not the cheapest instruments, but can be found in working condition and used for a few hundred dollars online said Glaze and Short’s Quality Lab Manager Leslie Nagy.

“But really — if you don’t do anything else, at the very least be clean and do microbiology testing,” they added.

What to read: In an age of being able to find knowledge easily, books and websites galore can also help increase quality.

Towns noted that the Brewing Science Institute website is a great source along with its “Brewers’ Laboratory Handbook” as a place to help set up a lab.

“Quality Management” by Mary Pellettieri is Towns’ go-to, indispensable book, she said. Walts echoed the book and noted that most local colleges and universities with fermentation science classes have become more and more the norm. Of course, courses from Siebel and UC Davis are the gold standard as well.

The Short’s team added a few other book resources: “Brewing” by Michael Lewis and Tom Young, and “Technology Brewing and Malting” by Wolfgang Kunze.

Where to join: Organizations such as the American Society of Brewing Chemists, the Brewers Association and Master Brewers Association of the Americas all help in providing information to its members.

“I highly recommend membership in one, and preferably all, of these organizations,” Towns said.

“Membership in the American Society of Brewing Chemists is critical for any brewery with a lab because their Methods of Analysis are the industry standard,” Walts said, “and the value of membership has skyrocketed since they moved the Methods online and included it with the cost of membership.”

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks