Beer has a long-standing tradition of purity, of doing things “the right way”, but it also serves many as a vessel for creativity and innovation, so how do brewers find a balance between the two? What place do added flavors, so popular in recent malt beverages and cocktails-in-a-can, have in the time-tested realm of brewing? A brief review of brewing history will depict a more fluid than rigid structure for proper brewing, and with that structure one can admit the use of newer ingredients, with flavors being among the most appealing and versatile.

The Reinheitsgebot, or Bavarian Purity Law, written in 1516 by Duke Wilhelm IV, is the gold standard for many regarding the “rules of beer”, and is still present in the law of brewing in Germany today. It originally stipulated that beer should be composed of only three ingredients: Barley, hops, and water. Upon the discovery of yeast and their function in brewing, the law was expanded to include yeast, as indeed they were in beer to begin with. In 1993, Germany passed The Provisional Beer Law, which allowed for the addition of sugar for flavor and coloring, the addition of stabilization and fining agents, and the use of grains other than barley. Again, there is a growth of the concept of “pure beer” to include new science, new technologies, and advancement of the product for consumers, without sacrificing quality.

Today, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) defines beer as “a beer… containing one half of one percent (0.5%) of alcohol by volume, brewed or processed from malt, wholly or in part, or from substitutes for malt.” This definition is clearly a far cry from the Bavarian Purity Law of 1516, and for many purists it swings too far towards inclusivity, but it speaks to the increasing fluidity of what “real beer” means. These vastly contrasting definitions share the goal of protecting the consumer from a fraud, from something other than what they paid for. Labeling adjuncts, labeling flavors, labeling non-grain sources of fermentable sugars, these are common practice for modern beverages so that consumers can decide what level of purity suits their tastes.

Pumpkin, guava, oak, vanilla, orange, coffee, chocolate, mint, and maple are all flavors that this author has seen, and tasted, used in beer in just the past month. Brewers continue to explore new flavor concepts, and ask of flavors common in candies, desserts, and cocktails, “why not in a beer?”

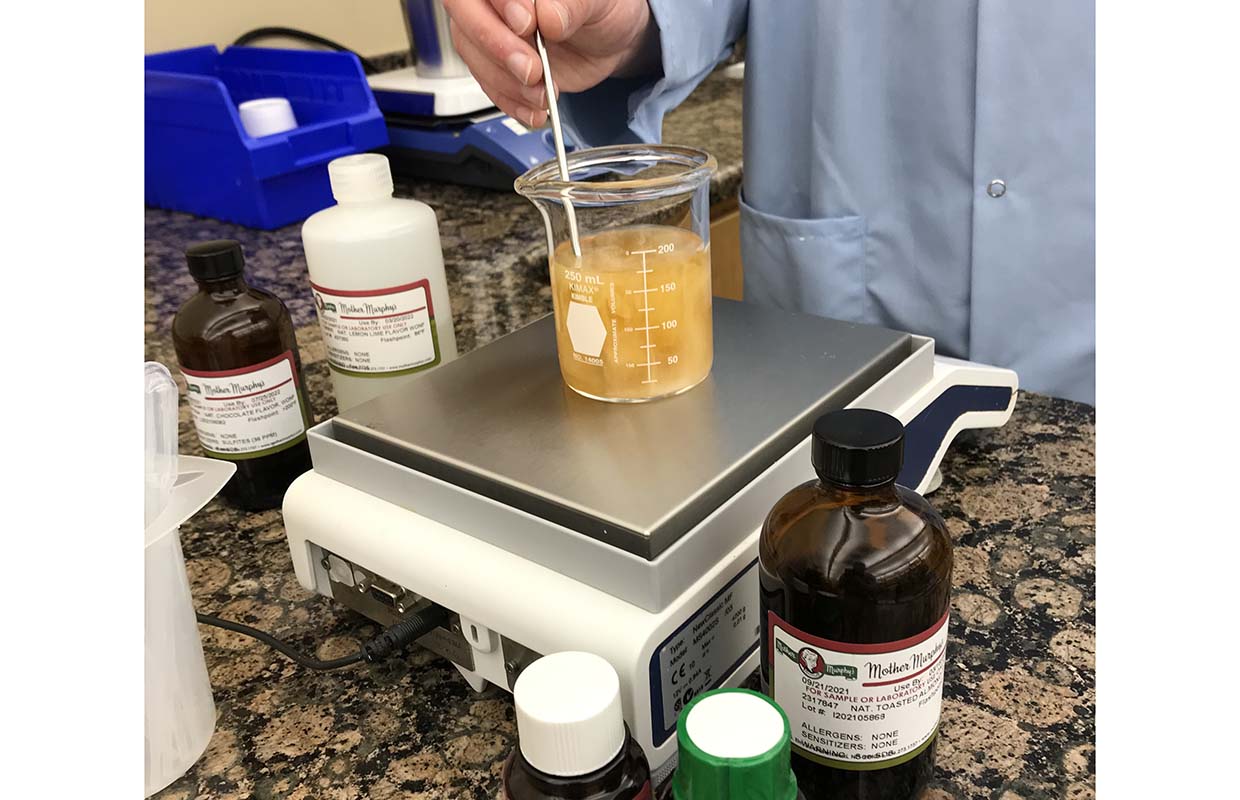

Mother Murphy’s Labs, a flavor house out of Greensboro, North Carolina, has recently created concepts for flavoring beer such as caramel coconut Stout, winter spice Porter, and apple cobbler Brown Ale, just to name a few. These flavors compared to their corresponding adjuncts (caramel, coconut, spices, apples, etc.) occupy a minute percentage of a product’s formula, they are shelf-stable, and they have a negligible impact upon ABV and gravity, while still contributing boldly to the flavor of the beer. Flavors are available with organic, natural, non-GMO, and gluten-free qualifications, so that consumers can maintain their diligence in clean-label shopping.

Brewers are also finding competition in lower calorie options on the market. For example, liquid refreshment beverages (which are non-alcoholic) have gone from accounting for 256.3 calories daily per capita in 2000 to just 183.9 in 2021. Beverages are healthier on-average, and consumers opt for zero-calorie options more often. Beer buyers see these options too, and brewers are exploring new ways to keep buyers engaged with creative products while keeping calories down. Flavors are a great way to do that.

From 1516 to today, beer is always evolving, always growing to incorporate exciting new elements. With a world of flavors available, and a world of beverages evolving, flavors might be central to the reformation of what “purity” means in brewing.

Be the first to comment