A clean and controlled fermentation doesn’t just make better beer for you. Doing it right from the start saves time, protects batch-to-batch consistency, improves shelf stability when needed, and maximizes your brewery’s raw material performance, which can help the bottom line.

From smaller brewpub setups to higher-volume systems, the quality of fermentation management can often be the quiet difference between a good beer and a great one.

Whether it’s through smarter yeast selection, tighter propagation cycles, more rigorous monitoring, or real-time sensory diagnostics, many are finding opportunities to optimize every stage of the fermentation curve.

Rethink Yeast Selection as Strategy, Not Just Supply

Choosing the right yeast strain is far more than matching your beer style to a spec sheet. It’s about knowing how a living organism performs under your specific conditions and tailoring your process to support it.

“Yeast is the name of the game,” said Erin Jordan, head brewer at Charlotte’s Resident Culture. “We’re stewards of a living organism, so choosing the right yeast and providing the right environment is paramount.”

While some breweries start with flexible, widely used strains like Chico or 34/70, the evolution of a brewery’s portfolio often leads to more nuanced decisions.

“We often trial similar strains from different suppliers to see which one gives us exactly what we’re looking for,” Jordan said. “We take copious notes and conduct sensory trials, comparing against previous runs before settling on a final choice.”

Jeff Donlon, owner of Sunken Silo Brewing, emphasized the balancing act between experimentation and practicality, noting how it can evolve as the brewery matures.

“Early on, we were buying fresh and dry yeast strain by strain, tuning recipes and learning what delivered the flavor profiles we wanted,” he said. “Eventually, we shifted to using primarily dry yeast for most ales because of its cost-effectiveness and reliability.

“Lagers still start with a fresh pitch, which we re-use up to seven times if viability holds.”

J. Warren Wilson III, brewmaster at Readington Brewery & Hop Farm, built out a dedicated house yeast program to balance for both scale and diversity.

“Now we select yeast not just for flavor but also for flocculation behavior, fermentation efficiency, biotransformation, and re-pitching bioavailability,” he said. “We propagate and maintain our primary strains regularly and use specialty yeasts more sparingly and briefly.”

For Pedal Haus head brewer Derek Hanson, consistency begins with smart harvesting.

“We collect the middle 80% of the slurry, throwing out the first and last 10% — to avoid poor performers,” he explained.

“For ales, we harvest between Day 5 and 7; for Lagers, Day 10 through 14. That timing has given us great results.”

Dial In Yeast Reuse with Tight Windows and Simple Tools

Yeast reuse isn’t just about saving money for savings’ sake; it’s about building consistency through repeatable processes. But it requires discipline and data.

“We don’t go beyond 10 generations for any strain,” Jordan said. “That gives us the best results in both flavor and fermentation performance. When we reuse, we adjust our schedule to use each harvest within a few days and store it in a sterile, cold brink.”

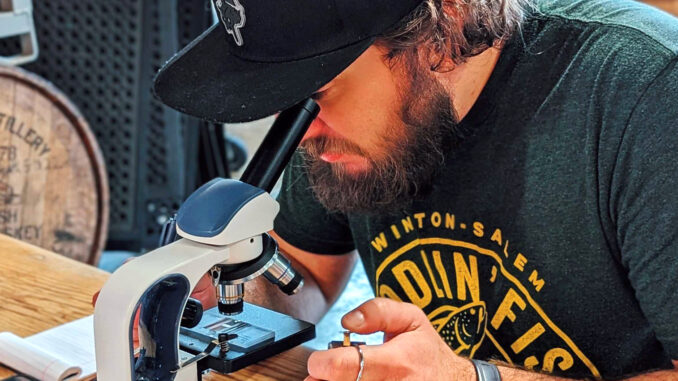

Resident Culture will evaluate each batch of yeast in the lab before pitching it into wort. Each strain and generation is examined under the microscope to assess cell viability, vitality, and density, while also checking for mutations or contamination.

Wilson outlined a more technical reuse program for Readington.

“We harvest 24–36 hours post-fermentation when viability peaks,” he said. “Yeast is stored at 34°F in sanitized brinks with gentle stirring. Depending on strain performance and sensory results, we limit re-pitches to between 5–8 generations.”

Sunken Silo’s approach is practical, with sensory checks leading the way.

“We generally avoid holding yeast in our brinks more than three weeks,” Donlon said. “If we need to stretch, we feed the slurry with fresh wort.”

While the New Jersey-based brewery doesn’t run in-house lab testing yet, he said they do rely on visual and aromatic evaluation before pitching.”

Microscope use is central to Wilson’s routine at Readington

“We perform cell counts, viability staining with methylene blue, and even budding rate evaluations on older brinked yeast,” he said. “The microscope is one of the most fascinating tools in brewing — you learn a lot just by looking at the ‘good little guys.’”

Resident Culture doesn’t propagate often, but when they do, Jordan said it’s usually with a fresh lab-grown pitch.

“We follow the 10% rule: pitching yeast into 10% of the total wort volume at a similar strength to the final batch,” she said. “This gives the yeast time to acclimate and begin cell replication before we add the rest of the wort 24 hours later.

“This method has worked well for us and helps save on costs.”

Use Daily Monitoring to Catch Small Problems Before They Grow

Every brewer we spoke with emphasized the importance of daily measurement. Analog or digital, you can’t improve what you don’t track.

“We monitor every tank daily—gravity, pH, VDK, crash temperature—and document everything,” said Jordan. “Automatic sensors can be expensive, but traditional lab equipment that’s calibrated and logged gives you precision without the price.”

Wilson agreed that hands-on monitoring trumps automation if you don’t have both: “We use thermometers, hydrometers, refractometers, pH meters, and daily sensory checks to monitor fermentation in real-time. This combination of analog and digital helps us stay aware, independent of Wi-Fi or battery power.”

Readington Brewery’s SOPs span from oxygenation to carbonation: “Our processes are ever-evolving, but we maintain strict procedures for each yeast strain and beer style. Diacetyl testing, fermentation ramps, and spunding protocols are updated whenever we introduce a new strain or scale up production.”

Pedal Haus uses traditional sampling, too. “We check gravity, pH, and taste throughout fermentation,” Hanson said. “Sometimes your palate is the best instrument.”

Sunken Silo is building toward formalized SOPs but is already exploring a low-cost digital solution. “We’re using Raspberry Pi and open-source software to create custom fermentation monitors. Most systems on the market are overpriced or don’t integrate well with what we use now,” Donlon said.

READ MORE: Learn From Your Fermentation

Train Your Senses to Spot Red Flags Faster

Knowing your yeast is one thing. Knowing when it’s in trouble is another. Often, sensory cues reveal issues before even instruments do.

Hanson said visual cues are the first check.

“The day after a brew, if I don’t see vigorous blowoff activity, that’s a red flag. If gravity hasn’t dropped at all, fermentation hasn’t started. But knowing your yeast helps. Some strains take off in hours, others are slower starters.”

Jordan echoed the value of daily tracking.

“We look for sluggish gravity or pH drops, atypical pH rises, and off-flavors like excessive diacetyl,” she said. “Daily tastings and forced diacetyl tests are standard for us.”

Donlon also puts sensory evaluation at the core.

“Sight and smell are our first lines of defense,” he said. “For Lagers especially, we run tight aroma checks for diacetyl and perform forced diacetyl tests as needed.”

Wilson’s approach is data-rich, but sensory-driven, as he said they watch for delayed CO₂ activity, stalled gravity, strange pH trends, sulfur or butter aromas, and excessive heat.

“We log and graph daily findings and compare them to historical curves,” he explained.

His team runs comprehensive testing during fermentation:

- Gravity and pH readings

- Forced diacetyl and acetaldehyde checks

- Cell viability mid-fermentation

- Triangle tasting between batches for consistency

“We also taste fermenters daily, evaluating esters, sulfur, CO₂ development, and overall cleanliness,” Wilson said. “This builds sensory experience and helps us catch issues before they impact quality.”

Fermentation doesn’t have to be a black box with little insight.

With the right yeast strategy, better reuse controls, strong monitoring routines, and sharper sensory habits, any brewer can troubleshoot issues early and enhance beer quality at every stage. Whether you’re running a full lab or relying on experience and analog tools, the key is consistency, which includes daily attention, intentional process, and a willingness to adjust when the beer says something’s off.

“Fermentation is where wort becomes beer,” Wilson said. “You can’t shortcut that transformation, but you can guide it better. Batch after batch.”

Love the advocacy for fermentation management and the power of the palate. Sennos just launched their SennosM3—an intelligent in-tank sensor that measures 8 fermentation parameters.